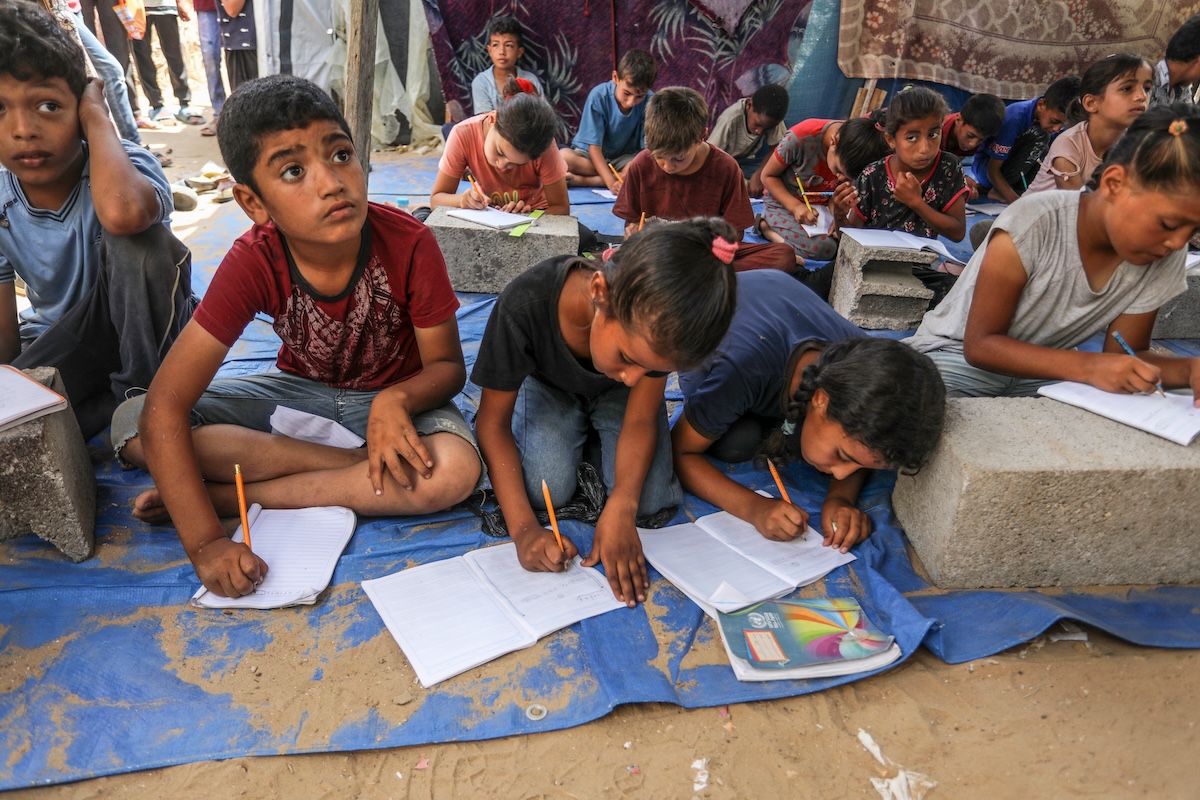

A young girl from Deir al-Balah, a displacement camp in Gaza, sat in an art therapy session. She refused all other colors, using only red. When asked by an implementing organization if she wanted other colors, she replied: “No, I saw the bombing, and there was blood everywhere.” She drew the same scene repeatedly, using only red.

After more than two years of the most recent conflict in Gaza, over 68,000 people have died, including over 20,000 children. While a ceasefire was signed in October 2025, the state of affairs in the region still seesaws between violence and calm. For Gaza’s 1.2 million children, physical survival alone is insufficient. The humanitarian sector must redefine its priorities to include mental health, child protection (protecting children from harm, abuse, and exploitation), and education alongside food, shelter, and health care as essentials in protracted crises.

A parallel protracted crisis in Gaza

Even as humanitarian actors deliver life-saving supplies, a parallel protracted crisis unfolds with devastating long-term consequences. Protracted crises are environments where populations face acute vulnerability to death, disease, and livelihood disruption over prolonged periods. Gaza fits this definition, having experienced decades of recurring violence.

UNICEF estimates nearly 100% of children need mental health support—unprecedented in humanitarian history. Some 17,000 children are unaccompanied or separated from families. Nearly 660,000 children have no access to education. Without timely intervention, the likelihood of intergenerational trauma increases, affecting not only children today but future generations. These crises compound over time: Unaddressed trauma becomes harder to treat as symptoms calcify into chronic conditions, educational gaps widen as children spend more time out of school, and protection risks increase as displacement continues.

Why sequential prioritization fails

Standard humanitarian response prioritizes food, water, shelter, and health care first, with mental health, child protection, and education addressed later if resources permit. This “basic needs first” framework reflects genuine constraints and the urgency of preventing starvation. But this sequential logic fails for children in protracted crises such as the one in Gaza for a few key reasons.

First, developmental windows are time-sensitive. Early childhood trauma affects brain architecture in ways that become increasingly difficult to reverse. Neural pathways formed during crisis—hypervigilance, dissociation, emotional dysregulation—become more entrenched with each passing month. What begins as acute stress calcifies into complex PTSD. Every month of delay transforms a treatable condition into one requiring years of intensive intervention.

Second, gaps compound exponentially. A child out of school for three months can catch up; but two years creates permanent learning gaps. Unaddressed trauma deepens, making interventions less effective and more costly. Protection risks escalate daily—separated children become more vulnerable to exploitation and potential recruitment into armed forces or groups. These aren’t parallel tracks addressed sequentially; they are interconnected crises that worsen in tandem.

Third, humanitarian services multiply each other’s effectiveness. A child with adequate food but untreated trauma experiences nightmares that disrupt sleep and impair concentration. Nutrition cannot translate into cognitive development when trauma goes unaddressed. Conversely, safety enables learning, education provides a stabilizing routine, and mental health support rebuilds family connections. Delaying “secondary” services like these appear to save resources short-term but dramatically increases costs over time—both in humanitarian spending for intensive treatment later and in lost human capital across generations.

This false economy demands a fundamental rethinking of what “lifesaving” means for children in protracted crises.

Redefining ‘lifesaving’

“Lifesaving” has been narrowly defined by the humanitarian architecture as preventing immediate mortality. As such, immediate funding needs go into the areas considered lifesaving, such as shelter, food, water, and health support from injury. Mental health, child protection, and education fall into a secondary category: important but not urgent; “recovery” rather than “response.” This framework must be revised.

For children, “saving a life” means more than biological survival. It means preserving the capacity for healthy development, learning, emotional regulation, and social connection. Child development doesn’t pause while humanitarian actors sequence their interventions. The brain architecture being shaped today will determine cognitive function, emotional health, and economic productivity for decades.

Reclassification has specific operational implications. These services must receive allocations from emergency response budgets, not just recovery funding that comes later. A recent analysis of humanitarian and development aid funding in crisis contexts found that, on average, about 3.8% of resources went to early childhood development, which includes health/nutrition, mental health, child protection, and education—but about 77% of this 3.8% went to health and nutrition. Mental health, child protection, and education specialists must deploy alongside physical health and nutrition teams, not as a second wave.

What humanitarian actors can do in Gaza and other protracted crises

A coordinated response maximizes limited resources and benefits to children. Three groups play pivotal roles therein and thus have roles to play in the reclassification of life-saving measures.

Donors should:

- Expand their definition of “lifesaving” to allocate resources across mental health, child protection, and education—not as afterthoughts receiving minimal funding, but as core emergency responses.

- Provide flexible, multi-year commitments that prioritize local actors best positioned to sustain these investments.

Humanitarian practitioners should:

- Enable local actors to lead implementation with international support, coordinating to avoid duplication.

- Track mental health and child protection as separate from broader protection and health clusters so it is clear how much funding is going to these critical areas.

- Integrate mental health, child protection, and education into other services to be more cost effective. For example, embed mental health staff in food distribution sites, integrate psychosocial support in temporary learning spaces, and provide child protection case management in health facilities.

- Scale up Palestinian capacity to deliver these integrated services.

Governments and political decisionmakers should:

- Create an enabling environment by letting local organizations lead rebuilding efforts.

- Open more border crossings and increase aid flows.

- Include mental health, child protection, and education as “essential services” in ceasefire agreements and rebuilding plans.

These three actors must work in concert. Money without access accomplishes nothing. Access without coordination wastes resources. Programs without sustained funding cannot scale to meet unprecedented need.

The humanitarian community has a choice: Continue defining “lifesaving” narrowly and watch Gaza’s children survive physically while continuing to suffer otherwise, or recognize that for children in protracted crises, mental health, child protection, and education are not secondary concerns—they are survival itself. The definitional shift costs nothing; the operational implications pay for themselves in reduced long-term intervention needs. The question isn’t whether we can afford to expand our definition of lifesaving. It’s whether we can afford not to.

link